Photo: IFC Films and Shudder

David Dastmalchian has a face for horror. It’s those eyes, slightly sunken but unnaturally bright, and gaunt cheeks that give him a stark, almost funereal aura. In another life, he might have been a mortician. Instead, he has become one of Hollywood’s most distinctive utility players.

Since his film debut as a paranoid schizophrenic on the Joker’s payroll in Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight, Dastmalchian has made the most of minor roles to bring a haunted humanity to one lost soul after another: a disturbed murder suspect in Denis Villeneuve’s Prisoners, a self-loathing supervillain in James Gunn’s The Suicide Squad, a guilt-ridden mental patient in Rob Savage’s The Boogeyman. He has stolen scenes in the past decade’s biggest blockbusters, from Villeneuve’s Dune to Nolan’s Oppenheimer, and appeared in all three Ant-Man films for Marvel.

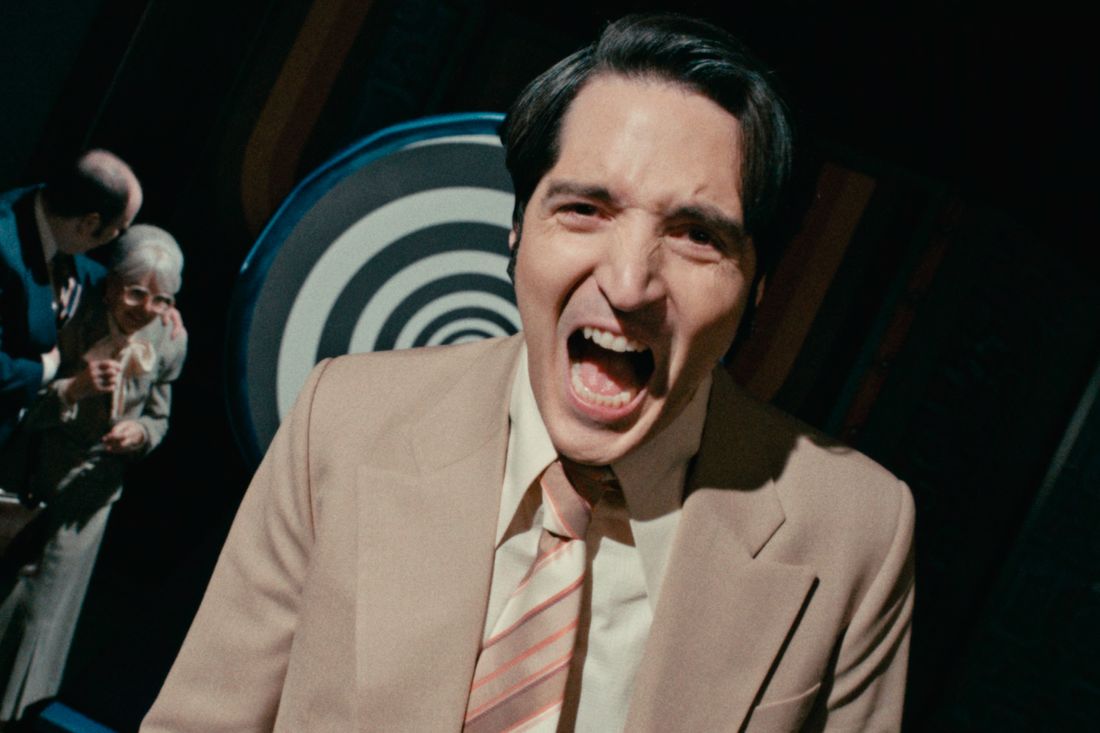

But the “scariest acting challenge” of Dastmalchian’s career to date has been playing Jack Delroy, the host of a fictional late-night talk show in Colin and Cameron Cairnes’s Late Night With the Devil (now in theaters, streaming on Shudder April 19). In this ’70s-set possession horror, Jack stages a Halloween special in hopes of turning around ratings that have been in free fall, only to unleash hell on his unsuspecting audience. A box-office hit that scored distributor IFC’s largest opening weekend ever, Late Night With the Devil puts Dastmalchian front and center in a rare leading role, allowing him to turn out a tour de force performance of outsize charisma and inwardly raging chaos. “I don’t think I’ll ever be quite the same,” he says.

Dastmalchian, a horror nerd who lives in Los Angeles with his wife and two children, is calling from his home office, where he’s surrounded by a magazine rack stuffed with vintage Creepy comics; signed Bela Lugosi, Lon Chaney, and Boris Karloff prints; and a framed 1971 issue of Look with Church of Satan founder Anton LaVey on the cover gripping a human skull. Horror has been a haven for the actor since, at 9 years old, he used to sneak down to his basement to catch Crematia’s Friday Nightmare. Broadcast on a local Kansas City station, the show featured radio host Roberta Solomon in character as vampy Crematia Mortem, who beckoned viewers into her haunted mansion’s living room and screened one classic horror film a week. When Dastmalchian moved to Chicago to study acting, he came across horror host Svengoolie and watched him loyally through a difficult period marked by depression, addiction, and homelessness.

“Horror was frowned upon in my house, so the love and humor of horror hosts like Crematia Mortem and Svengoolie helped carry me into and out of scary movies,” the actor says. “It became a subculture I geeked out over for years, and it’s inspired my own storytelling.” In the case of Late Night With the Devil, he means that literally: The Cairnes siblings read an article he wrote for Fangoria about his love of horror hosts and had producer Roy Lee reach out.

“I was flabbergasted by the vision,” Dastmalchian recalls. “But I kept thinking, Why the hell would they want me? As scared as I was of failing and letting everyone down because I didn’t know if I had it in me to manifest this character, I said, ‘Let’s do it.’ And then the journey began. It was so scary. I’m so glad I did it. I’m so proud of myself that I overcame my fear of this role and went for it because I think we’ve made a really special film.”

Playing a ’70s late-night-TV host must have been exciting given all the archival footage accessible from that era. How did you strike a balance between creating your own character and studying the likes of Johnny Carson and Dick Cavett?

If I were music right now, what would I sound like? Ambient, obscure, underground? Do I embody the energy, darkness, and tonality of Nine Inch Nails, Failure, or Depeche Mode? Say that’s in the marrow of my bones. Now imagine you tell me I’m playing the opposite of that, convincing everybody my tonality is Louis Prima with a big swing band. I was staring down this monolith of a character with dread. How could I get into this space and not look like some guy trying to be a talk-show host?

Every night before I went to bed, I’d watch Cavett, Carson, Conan, Letterman, Seth Meyers, Jimmy Fallon, Jimmy Kimmel, Don Lane, and Phil Donahue — all the footage I could get my hands on to let it permeate my subconscious with mannerisms, movements, patterns, rhythms, all this detail that felt to me so foreign. I went back to Don Lane a lot. He was a midwestern radio personality who became Australia’s Johnny Carson in the ’70s and ’80s. David Bowie was his last interview; he talked to Tom Waits in a famous interview that a lot of people think inspired Heath Ledger’s Joker. Lane had a proclivity to being open to the potential of the supernatural. He would bring on psychics and spoon benders but was different from American talk-show hosts in that he didn’t necessarily have them on as a gimmick. He gave them a chance to show they weren’t a joke.

You filmed on essentially a 360-degree set with three cameras running all the time. What was that like?

I’m a highly technical actor. I approach the work with specific attention to the idiosyncrasies of vocal expression, physical gesture, and little movements with hands, costume, or hair. Having three cameras meant there was no room for error or for me to rely upon the toolbox of go-to gestures and mannerisms of expressing certain emotional states of being I’ve used in the past. I had to develop a new set of windows to give the audience a view inside this character. Hopefully, if they’re thoroughly examining every angle of what it is I’m doing as this character, they can get lost in it. Hopefully, once the TV cameras go off and the film’s behind-the-scenes documentary cameras start to roll, I strip everything away and, as Jack, am as nakedly vulnerable as David would be in that given circumstance.

Throughout Late Night, supernatural moments materialize like cracks in Jack’s façade, disrupting his public persona and showing us his grief and desperation over the death of his wife and his declining viewership. Tell me about the layers of performance in this character.

I loved the presentational aspects of Jack Delroy, who he was at that time in 1977, trying to manufacture an impression of confidence, ease, and success while underneath being riddled with anxiety, depression, grief, and alcoholism. He’s a man on the verge of a nervous breakdown. You’ve got this almost Cassavetes-style character living in the template of a vintage Johnny Carson reality. At first, I saw no access point between David and Jack, but as I submerged myself into the script, I realized I didn’t know anybody who knew the core of this character better than me.

When I got this script, I was wrestling with unresolved grief, trauma, severe depression, and anxiety. I’m a recovering addict and alcoholic; I’ve had one nervous breakdown and been on the verge of another. All of those things I’m unburdening my shame about are still heavily weighed down by embarrassment, vulnerability, fear. Alongside that is this exterior persona I have given to the world as a part of myself that I am comfortable sharing: David, the character actor; David, the comic-book nerd who loves to talk about his favorite superheroes and villains, particularly the villains; David, the monster kid who wanted to be Lon Chaney, Vincent Price, or Christopher Lee; David, the cinema nerd who obsesses over the films of Michel Franco and people at the extremes of art house.

Here in this film is a man who, on the surface, is charming, witty, confident, brash, and in control in front of the camera — a feeling I very much understand. As soon as the camera stops, he’s barely keeping his lips above water, sucking in air, trying to keep things going. I know what it feels like to be in that challenging of a place mentally, spiritually, and physically. Once I gave myself over to the role, knowing what I wanted to achieve, that was my way in.

Being an actor requires an intense, overwhelming amount of confidence. I’ve always had the gift of a blind confidence in that I would try to share my ideas or tell my stories, which is so interesting because self-confidence and self-worth are two very different things. It wasn’t until this past year — with a lot of work I’ve done on myself in therapy — that I recognized how deeply low my well of self-worth has been. It’s a trigger for me to feel anxious and depressed, even in moments of great success and surrounded by people who love me very much. Jack is the extreme version of that: huge boatloads of self-confidence and internally he could not have a lower sense of self-worth, in his guilt over how little he was able to do for the love of his life as she was dying and his guilt over how much he’s put into the show that’s failing.

Count Crowley, your Dark Horse comic-book series, is all about midnight horror hosts and monsters. You once hosted the Fangoria Chainsaw Awards in character as Dr. Fearless, your own horror-host persona. Tell me more about this passion for horror hosts.

I’m a person so abjectly riddled with fear: fear of loss, abandonment, rejection. It’s daily work for me trying to be the person I want to be in this world, to learn to count on myself and support myself. One of the best ways I can do that is through courage and humor. I want to be a gateway for people going into the fun house of scares, shocks, and screams and then help usher them back out into the safety of the world, reminding them that we’re all in this together. One of the fun ways I do that, sometimes, is by adopting one of my alter egos I created and have been embodying: Dr. Fearless.

I originally started to flesh out the performative nature of Dr. Fearless because there isn’t much of a marketing budget in comics. And I thought if I could make my own old-fashioned horror-host commercials as Dr. Fearless talking about Count Crowley, maybe people would respond to that and it would be a good way to promote the comic. I’ve been doing it ever since. I dream of several things I want to manifest in my lifetime: I’d love to open a haunted house; I want to have an immersive live-action experience that evokes the feeling you get from going to see Sleep No More with the power of live haunts like Delusion. I would also love to have a weekly late-night show, Dr. Fearless in the House of Horrors, getting to show people all the classic monster movies. By the time I’m an old man putting on my Dr. Fearless makeup, the old horror movies I’ll be talking about will be Last Voyage of the Demeter, The Boogeyman, and hopefully, if I’m lucky, even Late Night With the Devil.

Photo: IFC Films and Shudder

Christopher Nolan gave you your first film role, in The Dark Knight, when you were working odd jobs in Chicago and still making your way as a theater actor. You recently reunited with him on Oppenheimer to play William Borden. What was it like working with him again at this stage in both your careers, and how did the experiences differ?

Before I met him, I had already had my perspective on cinema changed by his work, from Following and Memento through Batman Begins. For me, a lifetime comic-book collector, Batman Begins was an important film; Chris had a tonal approach to the material I’d never seen before, that I’d yearned for as somebody who’s a fan of The Long Halloween and A Death in the Family.

Then I had the opportunity to audition for the sequel to Batman Begins. I’m a struggling theater actor in Chicago, making $500 a week, occasionally booking a commercial, barely out of my time as a telemarketer and movie-theater usher. All rumors pointed to this film featuring my favorite comic-book character of all time: the Joker. All these years I’ve spent getting clean and sober, all this work I’ve been doing to develop myself as an actor, all these years dedicated to comics … it was my moment. I prepared the hell out of this audition for one of the masked bank robbers from the beginning of the film. John Papsidera, Chris’s long-time casting director, brought me into his office, with every other actor in Chicago, and saw my audition. He said, “This is amazing. I love what you’re doing. I can tell you’ve got a theater background. I need you to take all what you’re doing and put it in your eyes. That’s what Chris will look for.”

I came in the next day. I met Chris in person. He coached me through the audition. I went back to work; I was doing Othello at Writers Theater at the time. They shot the scene that week. I was devastated. Four months later, I got a call. I got to be in the film in an incredible role at a small but very important moment. Chris changed my life in ways I still come to recognize every day. The endorsement of a director like that, putting you into a film like that, giving you an opportunity like that — it just changes everything. It gave me an internal confidence and a boost to pursue acting in film.

All these years go by, and I’d never gotten to thank this genius, to ask, “Why did you pick me? How did this happen? Do you realize how much you’ve changed my life?” I’d wondered all those years if he remembered me. If he saw me in a film, would he even clock that it was the guy who had that little part in his movie? In December 2022, I got a call: “Chris has a role for you in his new film. Will you come down to Universal and read the script?” I mean, dude. Can you imagine? I read this manifesto of a script, then go into an office and see Chris sitting there with Cillian Murphy and Matt Damon. Chris sees me and invites me to sit down with him. It turns out he’s a huge fan of Denis Villeneuve, they’re friends, and he’s seen me in his films. He loved James Gunn’s The Suicide Squad and said how much he liked me as Polka-Dot Man. I got to thank him, not only in person but by again getting to be a part of a film that was so important to him, to bring everything I could to manifesting William Borden in a way that served his vision. It was one of the best experiences of my life.

The scene in Oppenheimer in which Borden recalls being in a plane, watching German V-2 rockets fly overhead toward England, is so crucial for your character, who became obsessed with the strategic implications of such weapons for U.S. security. It’s a scene echoed by the film’s final moments, when Oppenheimer imagines himself in the same cockpit watching the sky fill with nukes. What do you remember of filming that?

We’re in a shed outside of Los Angeles in pitch black. I’m in a cockpit, which I believe was cut out of an actual bomber, on a gimbal. This light’s going to travel past my field of sight as this missile carries its deadly explosives from Germany to London. I’m flying past it. As you said, that is a moment that changed William Borden forever and filled him with the wonder and the dread he needed to motivate his life’s work. Shooting that with Chris and his director of photography, Hoyte van Hoytema, knowing how that would be conveyed to Oppenheimer and impact him, penetrating into his consciousness as he considered the consequences of his work, I knew the magnitude of that moment.

You carry all of that with you up until the moment you’re starting the shot and then … you have to let it all go. You have to just be present, be a pilot, be a man seeing something for the first time. It’s so hard and scary because Chris is not going to settle for an actor performing or telegraphing. He needs me to strip away all of my bullshit. He helps me not try. He makes me feel trusted, that I can be there, uncomfortable in the energy I am carrying within me, and that the camera will capture it. That confident guidance is such a gift to an actor.

Late Night With the Devil is the first title from Good Fiend Films, the production company you launched last spring. How does it reflect the types of projects we can expect to see from you in the future?

Since I was a little kid, I’ve been filled with all of these complex fears and questions about the human experience and the universe, while being obsessed with the power of imagination as a place to get lost in. I’ve explored my journey as a storyteller from the stages of Chicago into independent cinema with films like Animals, Chronic, and All Creatures Here Below, where I could ask tricky, difficult questions without strictly needing to answer them. Juxtapose that with the grand-scale horror, superhero, and science-fiction filmmaking I’ve gotten to be a part of, from movies like Dune to The Suicide Squad to The Dark Knight and the Ant-Man franchise.

All of this I wanted to coalesce in my vision with Good Fiend Films, telling stories that wrestle with big questions through the lens of genre. Late Night With the Devil does that. I’m having a robust moment in comic-book publishing right now, going from my Count Crowley series with Dark Horse, which I’m aiming to adapt for film and television in the near future, to my new series from Todd McFarlane’s Image Comics, Knights vs. Samurai. I’ve been collaborating with my dear friends the Boulet Brothers, whose Halfway to Halloween special I produced. I have two films, five television series, multiple animation projects, and several unscripted projects, all of which with my very small but very mighty and capable team we want to bring to the world. I want the experience to feel like what you would get from spinning an old magazine rack, pulling off something creepy and getting lost in its pages, escaping to places that make you confront things you didn’t even realize you were capable of thinking about, while at the same time reminding you that you’re not alone. It’s the big, dark, scary trick of this universe that we are constantly pushed by all matter into this lie that we’re alone when all evidence points to the contrary. There’s so many more things we all have in common than those that separate us. As a storyteller, I can hopefully remind people, for even a fleeting second, that they’re not as alone as they think.